Where is the Kingdom of Cambodia?

Cambodia area:

total: 181,040 sq km (slightly smaller than Oklahoma)

land: 176,520 sq km

water: 4,520 sq km

Land use:

arable land: 20.44% permanent crops: 0.59% other: 78.97% (2005)

Population: 13,881,427

Median Age: 20.6

Growth: 1.78%

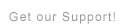

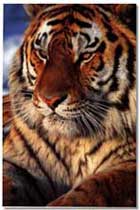

Short history of Cambodia

Government of Cambodia

Under the constitution promulgated in 1993 and subsequently

amended, Cambodia is a constitutional monarchy headed by a king; the

king is chosen by the Royal Council of the Throne from the members

of the royal family.

The bicameral parliament consists of a popularly

elected National Assembly with at least 120 members and a Senate with

no more than half the number of members of the National Assembly.

Members of parliament serve five-year terms.

The government is headed by a premier, who must have

the support of two thirds of the members of the National Assembly.

Current issues in Cambodia

Apathy and unawareness

There is no clear public or official desire for biodiversity conservation

or protected area management, in spite of government statements to

the contrary. There is no apparent public recognition that biodiversity

or protected areas contribute towards filling any meaningful human

needs. Rural people are not familiar with the concept of protected

areas. Absence of demarcation on the ground exacerbates the problem.

There is little or no public support; nor is there adequate public

information about protected areas and the laws that apply to them,

which might help to dispel current apathy and ignorance.

Lack of security

Continuation of civil war activity is a bar to any form of land use

management in affected areas. Land mines endanger human and wild animals

especially in northern areas.

Logging

Logging occurs in all protected areas, sometimes on an intensive scale.

Fifteen protected areas have commercially valuable timber species,

making them especially vulnerable. RCAF units entrusted with protecting

forest resources ignore or encourage logging. Land adjacent to protected

areas is often allocated for authorised timber extraction, providing

opportunities for logging companies to disguise unauthorised harvesting

in protected areas.

Legal ambiguity

Statutory laws for protected areas, by Decree or through the Law on

the Environment, are said to be unenforceable because the sub-decrees

required to set specific regulations in place have not yet been promulgated.

This seems questionable to the extent that MoE has at least some legal

claim to protected areas declared by Royal Decree, compared with trespassers

who have no legal rights of any sort. It appears, however, that MoE

makes little or no attempt to test the claims of those who exploit

resources in protected areas. That it fails to do so suggests a lack

of political will and a confused belief that once sub-decrees are

promulgated all with be well. In mitigation it is argued that if attempts

were made to test a claim, courts could not be relied upon to give

impartial judgements.

Corruption Massive corruption characterises

the timber industry and effectively neutralises what little law does

exist. ‘The co-Prime Ministers authorise virtually every concession,

illegal timber export and permits to confiscate old felled logs’ (Anon.

1998c). The same source also implicates the Prime Ministers of Thailand

and Viet Nam and the RCAF and observes that. DFW officials fail to

confront the issue of illegal logging, perhaps because of intimidation.

Abuse of wetlands

Wetland habitat is being lost through conversion of swamp to agriculture.

Forest removal around Tonlé Sap has led to increased siltation decreased

depth. The life cycles of fishes that move between main river systems

and spawning areas in upstream tributaries or swamp forests are being

disrupted.

Inadequate resources

Most protected areas are unmanned. Those that are manned are ill equipped

and without transport other than shared bicycles. Most protected areas

are remote, access is difficult and security is poor. Malaria is a

constant threat. Most areas lack a permanent ministerial presence

so that capacity for enforcing those laws that do exist is low. Lawlessness,

intimidation and corruption are rife.

Inadequate mechanisms for coordination

Co-ordination between agencies responsible for different aspects of

land use appears to be absent or inadequate.

Local pressures

Most (perhaps all) protected areas have human settlements and associated

shifting cultivation within. People living in or nearby protected

areas harvest NTFP (including wild animals) from within. They also

cause fires that thin out the fire tolerant dry dipterocarp forests

year by year. Not all people originated locally. Some are outsiders

who have come there to find land and access to forest resources. When

conflicts arise over land use local politicians side with people who

are cultivating or using protected areas in other ways.

Illegal hunting is widespread wherever sufficient

animals remain to make this a worthwhile activity. According to an

article in the Cambodia Daily of 18 Feb 1999, poachers have taken

to using homemade explosives to trap and kill tigers, chiefly to harvest

their bones and skins. The economic value of a single tiger’s by-products

is estimated to be at least $1,500 to the middlemen who smuggle them

across international borders, which is more than four times average

annual income.

Size of the protected area system

The protected areas have been selected with biodiversity conservation

and representativeness firmly in mind resulting in an admirably designed

system that covers over18 per cent of total land area (16 per cent

of IUCN management categories I to IV). However, it is doubtful whether

any other country in the world can match this and it must seriously

be questioned whether such an enormous system can be put under effective

control in the foreseeable future, while rising rural populations

continue to exert increasing demands upon unoccupied land, exacerbated

by lawlessness and apparent lack of any significant public concern.

Dwindling donor support

Donor support accounts for 90 per cent of all protected area funding.

Continuance beyond 1998 is in jeopardy.

Uncontrolled wildlife trade

The cross border trade described above adds to Cambodia's natural

resource impoverishment.

Environmental activities

in Cambodia

The Department of Nature Conservation and Protection under

the Ministry of Environment has the responsibility for overseeing

these 23 protected areas and 3 Ramsar sites, two of which are contained

within the 23 protected areas. Combined, all of these areas cover

32,289 km².

Unrelated to the Law on the Environment, provisions for protected

areas were declared by Royal Decree 'Creation and designation of protected

areas', 1 November 1993. Levels of protection are defined by Ministerial

decree (Prakas Ref. 1033). However, these only state the principles

for protected areas: a further Sub-Decree is required to establish

their provisions in law, and this has yet to be drawn up. Furthermore,

the laws cannot be enforced until protected area boundaries are demarcated

on the ground. This would be a considerable undertaking. The combined

perimeters of the four national parks presently under some form of

management (Bokor, Kirirom, Verachay and Ream) is at least 600 km,

much of it traversing rugged inaccessible terrain. Completion of boundary

demarcation for even those four areas may be several years in the

future.